CATA astronomer participates in discovery that challenges the formation of galactic clusters

With the presence of the Center's Associate Researcher, Manuel Aravena, this finding provides new evidence of the origin and evolution of these structures in the early Universe.

An international team of astronomers has detected the oldest hot intracluster atmosphere ever observed, revealing a huge thermal reservoir in a forming galaxy cluster: SPT2349-56. The finding challenges current models of how galaxy clusters formed and evolved in the early Universe.

The study, published in the journal Nature, features the participation of astronomer Manuel Aravena, Associate Researcher at the Center for Astrophysics and Associated Technologies – CATA (ANID Basal Center) and professor at Universidad Diego Portales (UDP), along with Manuel Solimano and Ana Posses, who were students at CATA and UDP during the course of this research. The work was led by Dazhi Zhou, a doctoral candidate at the University of British Columbia.

What is SPT2349-56 and why is its discovery significant?

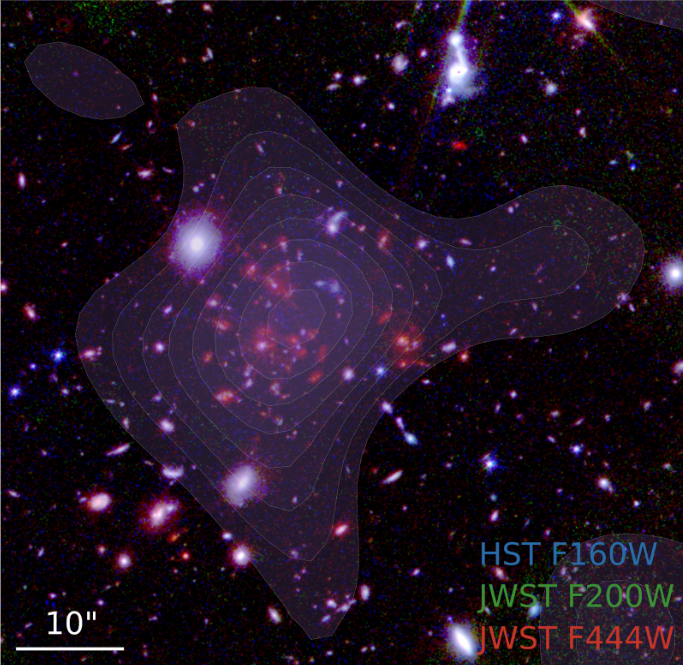

SPT2349-56 is an extremely massive and compact proto-galaxy cluster, observed when the Universe was only 1.4 billion years old, equivalent to 10% of its current age. It is one of the densest and most active structures known at such an early cosmic epoch, harboring dozens of galaxies with intense star formation, along with several supermassive black holes in a rapid growth phase.

What is particularly relevant about SPT2349-56 is that it represents a very early stage in the formation of galaxy clusters, which are the largest gravitationally bound systems in the current Universe. Until now, it was thought that in these early stages, the intracluster gas was not yet sufficiently hot or organized. This study shows that, surprisingly, the cluster already contains a massive reservoir of hot gas, challenging that traditional view,” explains Manuel Aravena.

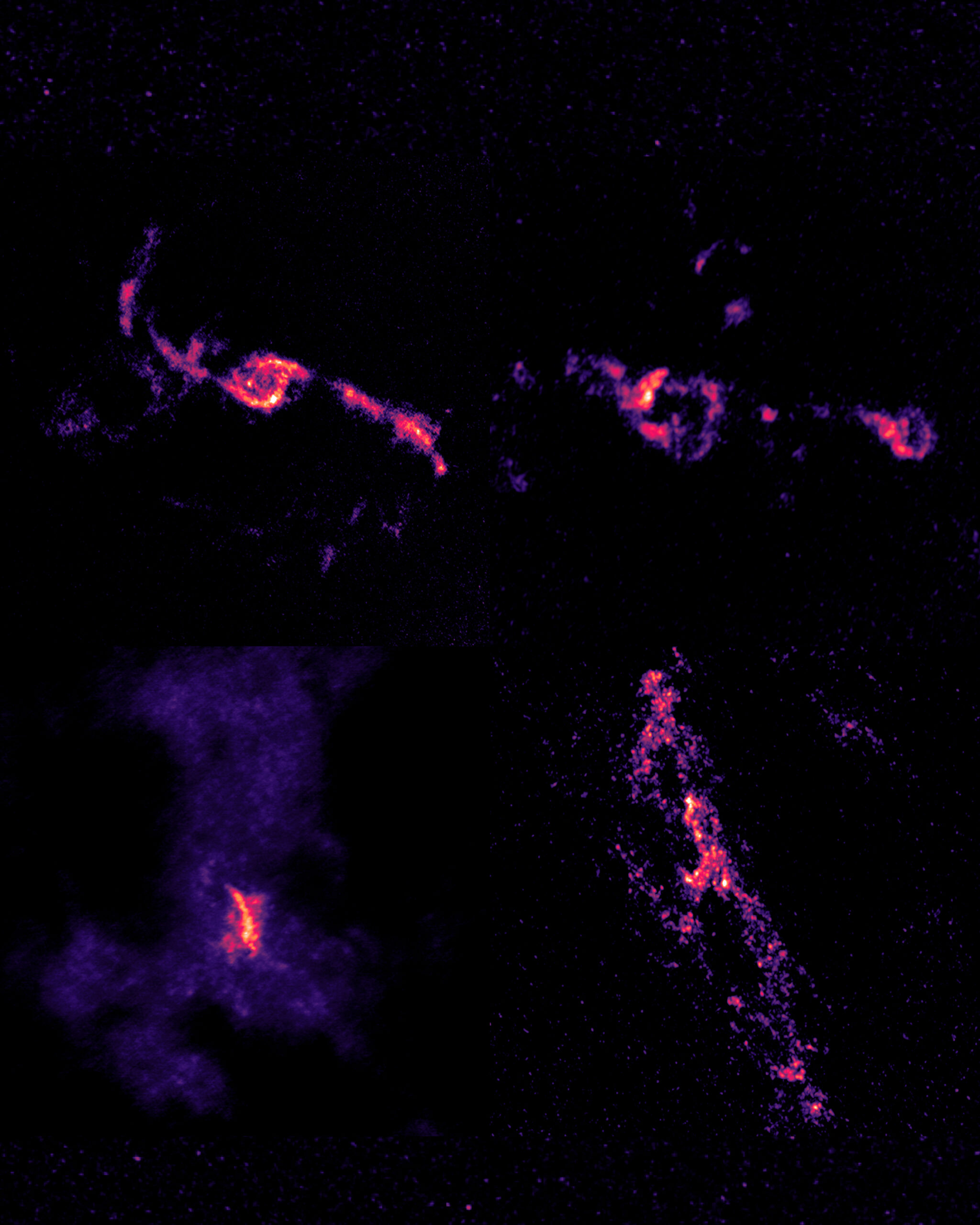

To make this discovery, the research team used the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) radio telescope, employing an unusual observation technique called the Sunyaev-Zel’dovich thermal effect (tSZ), which does not detect the light emitted by the gas, but rather a subtle “shadow” that the hot gas casts on the fossil radiation from the Big Bang: the cosmic microwave background.

This effect does not lose intensity with distance, making it a unique tool for studying hot gas, even in the very early Universe. ALMA’s sensitivity and resolution made it possible, for the first time, to isolate and directly measure this effect in a proto-cluster at z>4 (a very early age of the Universe), revealing the presence of gas that is much hotter and more energetic than expected,” explains the CATA researcher.

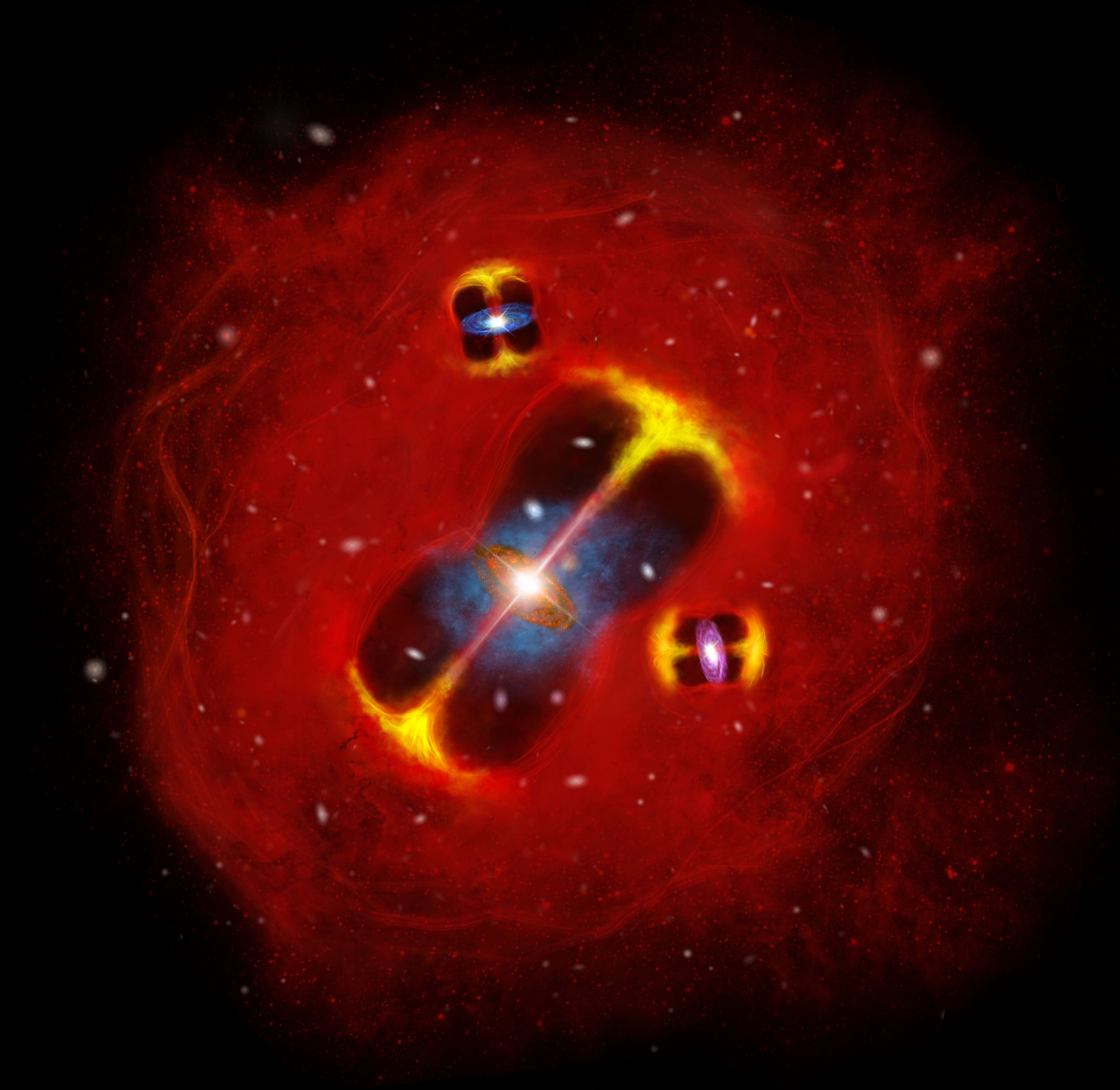

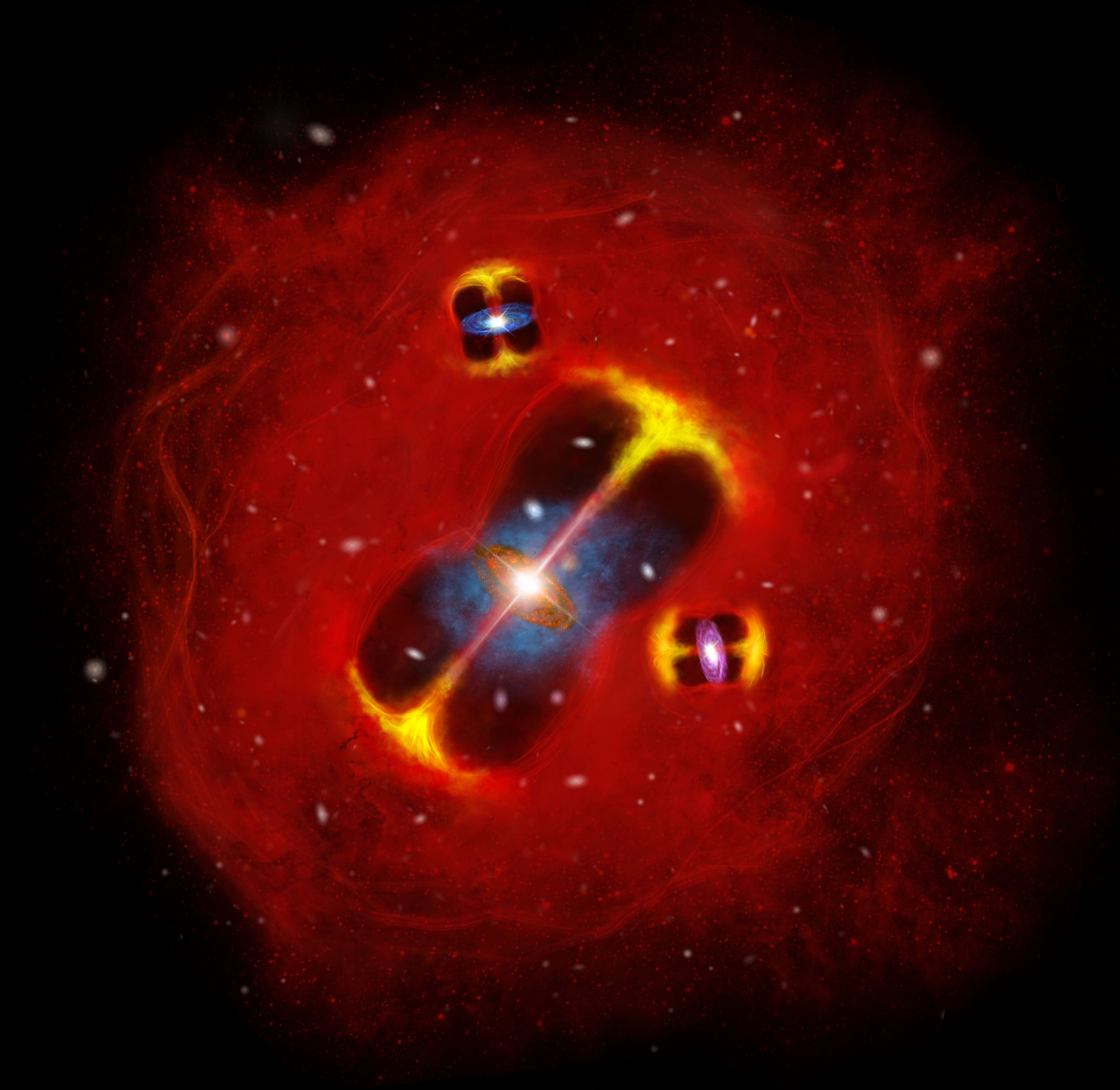

Regarding the relationship between cluster formation and the energetic processes associated with galaxies and black holes, Aravena adds that “this study reinforces the idea that the evolution of clusters and their galaxies is deeply coupled. In SPT2349-56, intense star formation coexists with multiple active supermassive black holes, some of which emit powerful radio jets.”

The results indicate that the energy released by these black holes can be transferred very efficiently to the surrounding gas, heating and pressurizing it (increasing its pressure) before the cluster is fully formed. “These objects not only regulate the evolution of their host galaxies, but also directly influence the thermal fate of the entire cluster,” adds Aravena.

Prior to this discovery, it was assumed that in the early cosmic epochs, galaxy clusters were still too immature to have fully developed and heated their intracluster gas. No hot atmosphere had been directly detected in clusters during the first 3 billion years of the Universe’s history.

Current models predict that, at such early stages, clusters should contain relatively cold, low-pressure gas, which gradually heats up as the structure grows through gravitational accretion. However, in SPT2349-56, there is an excess of thermal energy of at least one order of magnitude (a factor of 10x) compared to what gravity alone can explain,” explains the UDP academic.

The participation of Manuel Aravena alongside his students Manuel Solimano and Ana Posses, and the use of the ALMA radio telescope, demonstrate the scientific and educational impact of the Chilean astronomical ecosystem, especially organizations such as CATA and UDP.

“It reflects the capacity of our country’s institutions to train advanced human capital that actively contributes to cutting-edge discoveries, in collaboration with international teams and using world-class infrastructure such as ALMA. It is a concrete example of how investment in training and scientific collaboration generates visible returns in high-impact science,” the astronomer points out.

New lines of research and next steps

The results from SPT2349-56 suggest that processes such as supermassive black hole activity may be heating gas very efficiently and very early on, something that is not fully incorporated into current cosmological simulations. This opens up new lines of research, both observational and theoretical, focused on understanding when, how, and how common this “overheating” phase is in younger galaxy clusters.

Aravena mentions that one of the main challenges will be “determining how common this type of hot gas is in proto-clusters in the early universe.” This raises the question of whether, in this case, it is something exceptional or a brief but widespread phase in cluster formation.

“In the future, it will be key to combine tSZ observations with ALMA and cosmic background experiments, together with data from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and X-rays, to trace the thermal evolution of intracluster gas over cosmic time. At the same time, theoretical models will need to incorporate early energy feedback mechanisms more realistically. SPT2349-56 thus becomes a unique laboratory for understanding how the largest clusters in the Universe are born,” concludes the CATA researcher.

Recent news

-

Publicado el: 09/01/2026CATA astronomer participates in discovery that challenges the formation of galactic clusters

Publicado el: 09/01/2026CATA astronomer participates in discovery that challenges the formation of galactic clusters -

Publicado el: 08/01/2026Meet: Valeska Molina, Regional Ministerial Secretary for the Antofagasta and Atacama regions at MinCiencia

Publicado el: 08/01/2026Meet: Valeska Molina, Regional Ministerial Secretary for the Antofagasta and Atacama regions at MinCiencia -

Publicado el: 05/01/2026New General Manager takes over institutional leadership of CATA

Publicado el: 05/01/2026New General Manager takes over institutional leadership of CATA -

Publicado el: 22/12/2025International study reveals that black holes feed selectively

Publicado el: 22/12/2025International study reveals that black holes feed selectively -

Publicado el: 20/12/20253I/ATLAS: the interstellar comet approaching Earth and what is known about it

Publicado el: 20/12/20253I/ATLAS: the interstellar comet approaching Earth and what is known about it

Categories list

- Acknowledgments 21

- Astrobiology 7

- AstroCluster 1

- Black holes 20

- Corporativo 60

- Cosmology 5

- Descubrimientos 23

- Disclosure 74

- Exoplanets 14

- Extension 7

- Galaxies 22

- Galaxies formation 6

- Inter y Transdisciplina 4

- Local Universe 17

- Publications 6

- Sin categorizar 34

- Solar System 23

- Stellar formation 8

- Technology 16

- Technology Transfer 19