International study reveals that black holes feed selectively

Observations with the ALMA radio telescope reveal that supermassive black holes feed selectively in merging galaxies.

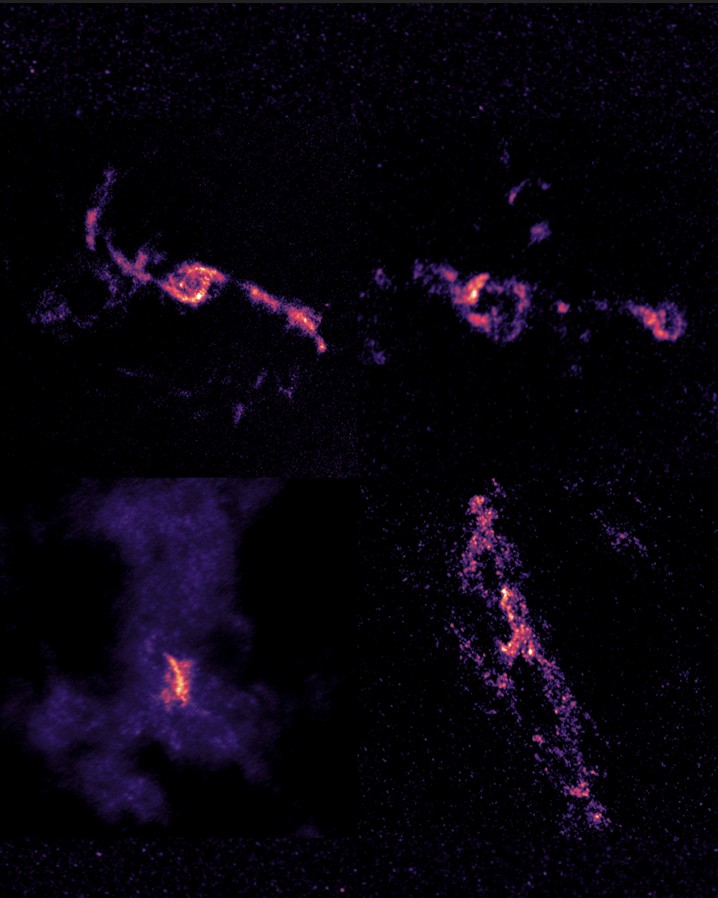

New international research reveals one of the most detailed looks yet at how supermassive black holes feed in merging galaxies. Based on high-resolution observations made with the ALMA radio telescope, the study reveals that even when there is abundant gas available within the black holes’ sphere of influence, these extreme objects do not begin to consume the gas immediately or continuously, but rather do so selectively.

The research involves the participation of the principal investigator at the Center for Astrophysics and Associated Technologies – CATA (ANID Basal Center) and academic at the University of Tarapacá (UTA), Ezequiel Treister, and Chilean astronomer at the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO) in the United States, Loreto Barcos-Muñoz, and is led by astronomer and doctoral student at the University of Virginia, Makoto Johnstone.

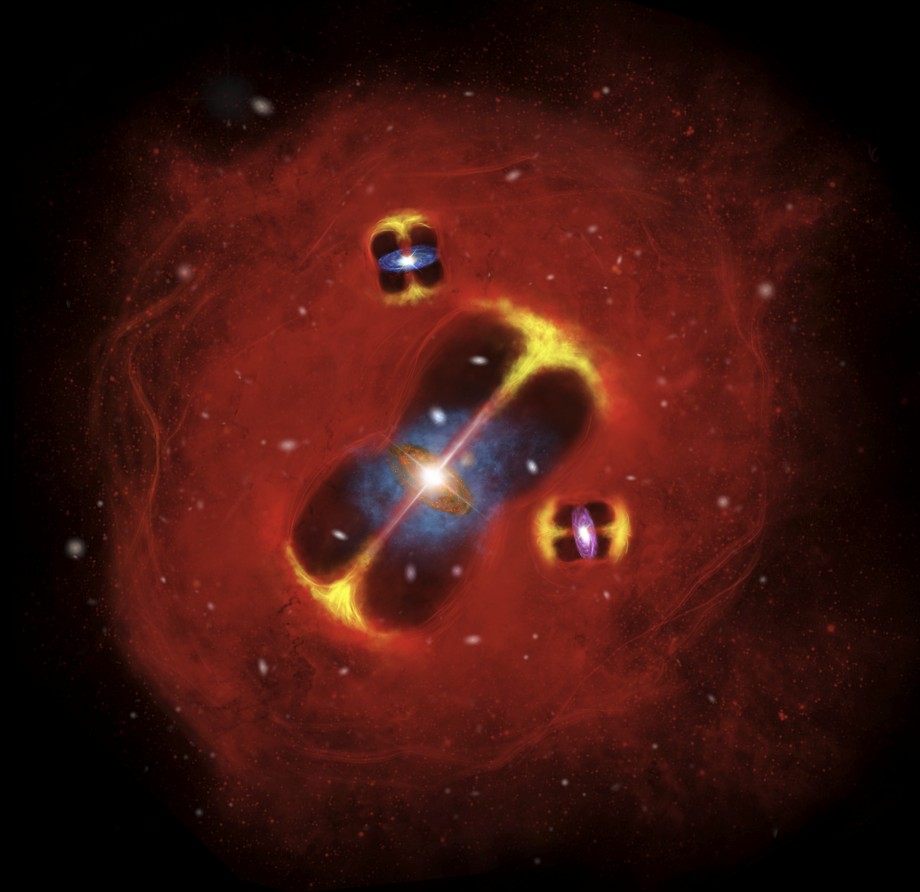

The team analyzed seven nearby galaxies that are in the process of colliding. In some of them, two black holes can be observed at their centers, both growing and emitting X-rays, while in others only one is detected. Thanks to high-resolution observations, astronomers examined in detail what is happening in the immediate vicinity of these black holes and tracked the movement of the gas surrounding them. This allowed them to identify the material with the most chaotic dynamics, which is their main source of fuel.

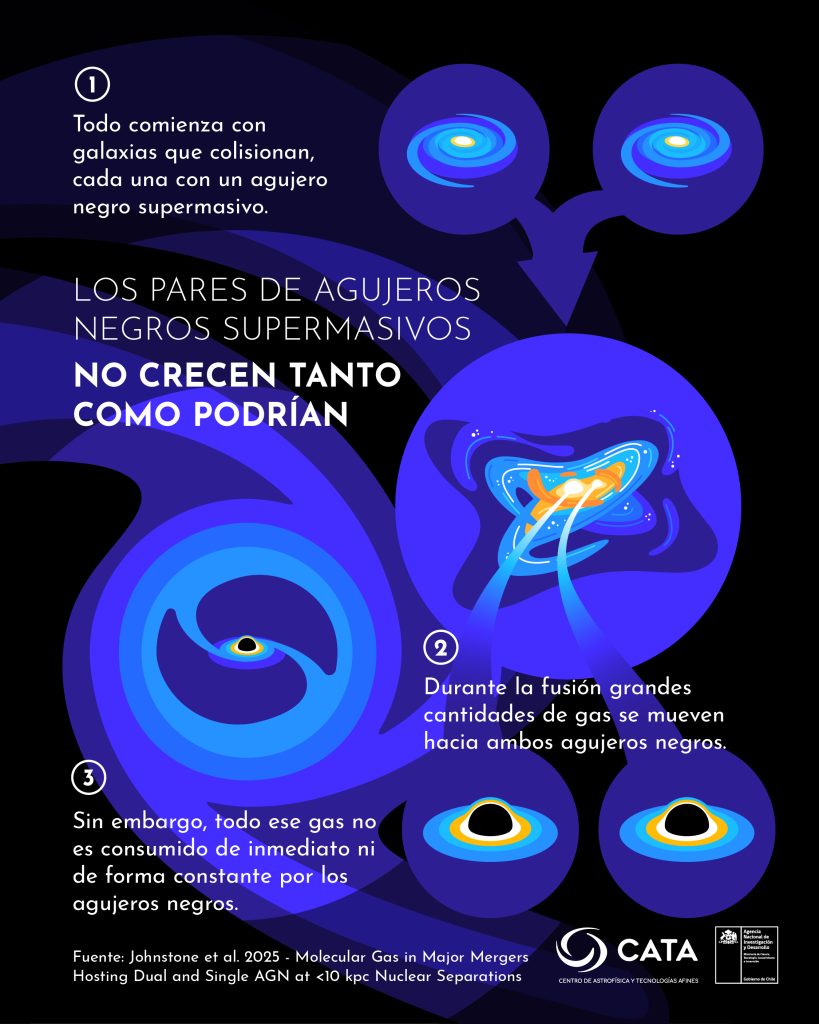

One of the most relevant findings of the study is that the presence of large amounts of gas does not guarantee that a black hole is actively feeding. Despite being surrounded by abundant material, many of these black holes only “consume” a small fraction of the available gas. In simple terms, the results show that black holes are highly selective: they feed only when conditions allow, not necessarily when there is more gas around.

“Galaxies contain a black hole at their center, which was not necessarily born supermassive, but grew over time by feeding on the gas and dust around it, a process we call accretion,” explains Ezequiel Treister, Principal Investigator at CATA.

“Although galaxy mergers concentrate large amounts of gas in their central regions, only a very small fraction of that material ultimately feeds the black hole,” adds Loreto Barcos-Muñoz, a Chilean astronomer at the NRAO.

This behavior is observed in highly dusty and turbulent environments. At many wavelengths, dust prevents direct observation of what is happening in the galaxy’s core, obscuring the black hole’s activity. However, thanks to ALMA’s capabilities, which observe at longer wavelengths and have exceptional angular resolution, it is possible to see through the dust and study the cold gas in regions very close to the black hole. This unique capability made it possible to demonstrate that the growth of a supermassive black hole depends not only on the amount of gas available, but also on much more complex processes, such as the loss of angular momentum of the gas, brief episodes of accretion, and strong levels of obscuration.

Although galactic mergers concentrate gas toward the center, the study shows that the presence of gas very close to the black hole does not guarantee efficient feeding at that moment. The gas may be displaced, rotating, or dynamically disconnected from the black hole, suggesting that accretion is a highly variable and episodic process. “A study of this type is only possible thanks to the capabilities provided by ALMA,” explains Ezequiel Treister.

Chilean relevance in the study

The study also highlights Chile’s role in global astronomy. In addition to the aforementioned team, this research includes other CATA researchers, including Franz Bauer from the University of Tarapacá (UTA); Ignacio del Moral-Castro, from the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile (UC); and Claudio Ricci, who was a member of the institution during the research period, consolidating the Center as a high-impact international research center and a relevant player in the study of supermassive black holes.

On the other hand, the ALMA radio telescope, located in the north of the country, is a key infrastructure for this type of study, and the active participation of researchers trained or affiliated with Chilean institutions demonstrates how the country not only hosts the most advanced telescopes in the world, but also leads the science that is done using them.

“These are very dusty and highly turbulent systems, where we cannot directly observe the growth of the black hole at other wavelengths. However, with ALMA we observe longer wavelengths and have incredibly high angular resolution, which allows us to observe directly, through the dust, on a very small spatial scale. This is something that only this radio telescope can currently achieve,” explains Makoto Johnstone, lead author of the research.

The study also highlights notable scientific careers in our country, as Makoto Johnstone completed part of his training at UC alongside Ezequiel Treister during the research process, while Loreto Barcos-Muñoz, a Chilean astronomer, currently works at the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO) in the United States.

“This work is the result of years of training and collaboration between researchers who are now spread across different countries, but who share a common academic history,” says Ezequiel Treister.

What’s next

According to the researchers, the next challenge is to expand the sample of galaxies studied and combine ALMA observations with data from other observatories, such as the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST).

The goal is to continue studying energy emission in AGNs in greater depth and to better understand the conditions under which gas finally crosses the final threshold and feeds the supermassive black hole. In this regard, they say that “the next step is to observe more systems and continue to increase the sharpness of our data, to understand when and how gas actually reaches the black hole.”

Recent news

-

Publicado el: 30/01/2026Looking ahead to the next five years: Galaxies Area meets to share progress and strengthen research

Publicado el: 30/01/2026Looking ahead to the next five years: Galaxies Area meets to share progress and strengthen research -

Publicado el: 29/01/2026Will Earth have two moons until 2083? The idea behind object 2025 PN7

Publicado el: 29/01/2026Will Earth have two moons until 2083? The idea behind object 2025 PN7 -

Publicado el: 27/01/2026Public domain report highlights technologies born from astronomy

Publicado el: 27/01/2026Public domain report highlights technologies born from astronomy -

Publicado el: 20/01/2026Teletón patients were introduced to astronomy through CATA workshops

Publicado el: 20/01/2026Teletón patients were introduced to astronomy through CATA workshops -

Publicado el: 19/01/2026Astronomical technology was part of Congreso Futuro 2026

Publicado el: 19/01/2026Astronomical technology was part of Congreso Futuro 2026

Categories list

- Acknowledgments 22

- Astrobiology 8

- AstroCluster 1

- Black holes 19

- Corporativo 62

- Cosmology 5

- Descubrimientos 25

- Disclosure 77

- Exoplanets 15

- Extension 6

- Galaxies 23

- Galaxies formation 7

- Inter y Transdisciplina 4

- Local Universe 17

- Publications 7

- Sin categorizar 36

- Solar System 23

- Stellar formation 8

- Technology 18

- Technology Transfer 20